Patient Bill Of Rights

As a patient, you have certain rights when you visit a doctor or hospital. Become familiar with your rights – listed...

%20(2)-1.png?width=475&height=199&name=Email%20Header%20-%20Dr%20Phil%20(1920%20x%20800%20px)%20(2)-1.png)

Dr. Phil McGraw, acclaimed host, and the 26-year trusted voice in America, unveils MERIT STREET MEDIA™, a new network of essential news and entertainment delivering common sense television you can use. Programming, to be announced, will include Dr. Phil and a diverse and respected group of household names.

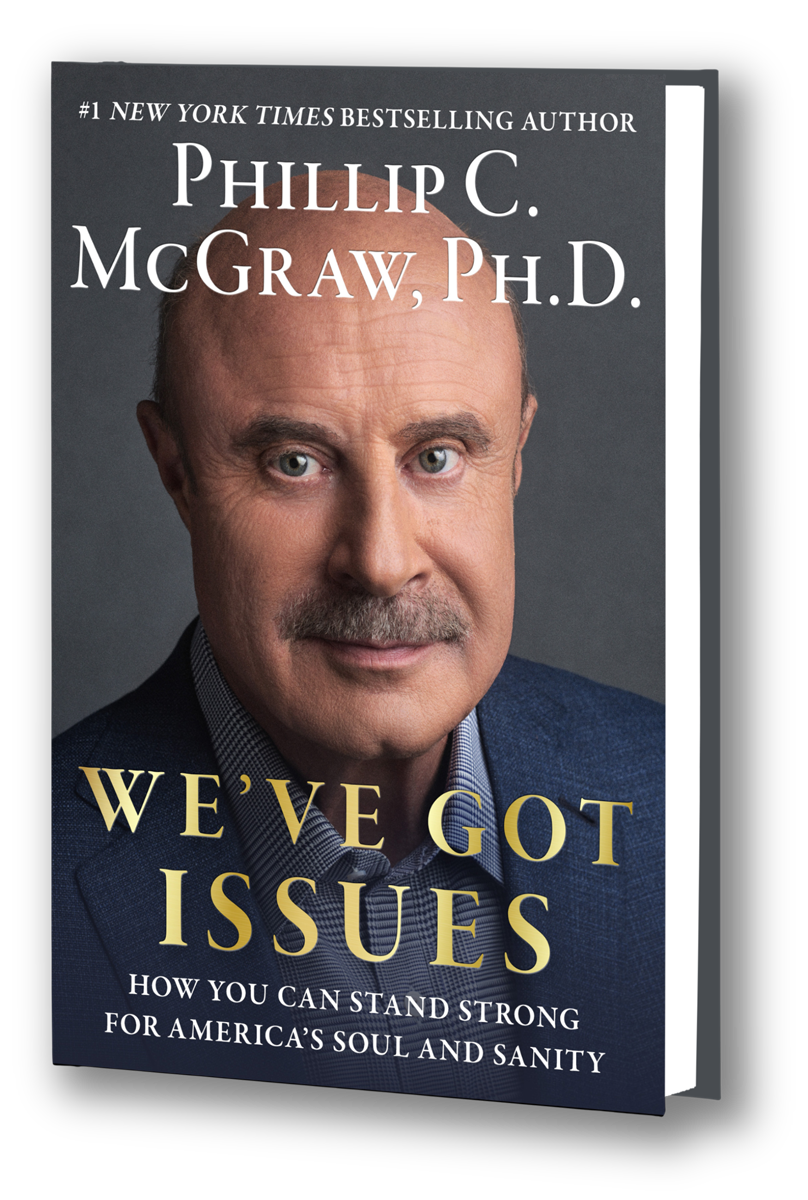

From the #1 New York Times bestselling author and beloved television host comes We’ve Got Issues, How You Can Stand Strong for America’s Soul and Sanity, a new book on how to come home to our core values, fortify our families and re-embrace self-determination and self-governance.

As a patient, you have certain rights when you visit a doctor or hospital. Become familiar with your rights – listed...

Are you seeking answers to your health insurance questions? We turn to insights from Rhonda Abdalla, a licensed...

When it comes to healthcare costs, there’s a popular way to get additional benefits and protect yourself from high...

Even when life feels busy, don’t forget to train your brain just like you exercise any other part of your body!

“It’s...

Making time for fun in your life on a regular basis is really important for your emotional and mental well-being,” Dr....

In The 20/20 Diet: Turn Your Weight Loss Vision Into Reality, Dr. Phil shares the results of a national survey on the...